Haplogroup O2b (Y-DNA)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2006) |

Haplogroup O2b (SRY465, a.k.a. M176) is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. It is a descendant haplogroup of Haplogroup O2. Haplogroup O2b is found mainly in the northeastern parts of East Asia, from the Daur people of Inner Mongolia to the Japanese of Japan; however, haplogroup O2b has also been found at significant frequency among some populations of Southeast Asia, including those of Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam and from many people in Bangladesh.[1] This haplogroup is found with its highest frequency and diversity values among modern populations of Japan and Korea and is absent from most populations in China.[citation needed]

[edit] Subgroups

The phylogeography of Haplogroup O2b suggests a very ancient origin in Manchuria, followed by a long period of isolated evolution and population increase within the Korean Peninsula. Only the most ancient branches of this haplogroup, which are labeled as Haplogroup O2b*, have been detected among the indigenous populations of Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, and even then they are found only at very low frequencies. Haplogroup O2b* Y-chromosomes have been detected at a similarly low frequency among the Koreans, but Korean males display a very high frequency of a derived subclade, Haplogroup O2b1* (P49). In fact, Haplogroup O2b1* comes close to being the modal Y-chromosome haplogroup in Korea, occurring in approximately 35% of all Korean males.

A subclade of Haplogroup O2b1, namely Haplogroup O2b1a (47z), is found at a fairly high frequency among the Yamato people and Ryukyuan populations of Japan. Haplogroup O2b1a has been detected in approximately 22% of all males who speak a Japonic language, while it has not been found at all among the Ainu or Nivkhs of the northern extremes of the Japanese Archipelago. Based on the STR haplotype diversity within Haplogroup O2b1a, it has been estimated that this haplogroup began to experience a population expansion among the proto-Japanese of approximately 4,000 years ago, which makes it a good candidate for a marker of the intrusion of a Neolithic population of the prehistoric Korean Peninsula into the southwestern parts of the Japanese Archipelago. However, the parent haplogroup, O2b1*, is also found among Japanese, although at a relatively low frequency of approximately 4% to 7%, and the descendant haplogroup O2b1a is either completely absent from or found at only extremely low frequency (which could represent historical Japanese admixture) among samples of modern Koreans, which suggests the possibility that Haplogroup O2b1* might have colonized the Japanese Archipelago much earlier, with the subgroup O2b1a subsequently evolving within the proto-Japanese-Ryukyuan population of the western parts of the archipelago.

[edit] References

- ^ Han-Jun Jin, Kyoung-Don Kwak, Michael F. Hammer, Yutaka Nakahori, Toshikatsu Shinka, Ju-Won Lee, Feng Jin, Xuming Jia, Chris Tyler-Smith and Wook Kim, "Y-chromosomal DNA haplogroups and their implications for the dual origins of the Koreans," Human Genetics (2003)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_O2_(Y-DNA)

Although Haplogroup O2 is not found so frequently in modern human populations as its brother clade, Haplogroup O3, it is notable for the peculiarities of its geographical distribution. Like all clades of Haplogroup O, Haplogroup O2 is found only among the males of modern Eastern Eurasian populations. However, unlike Haplogroup O3, which is shared in common by almost all populations of Eastern Eurasia as well as many populations of Oceania, Haplogroup O2 is generally found only among certain populations, such as the Austroasiatic peoples of India, Bangladesh and Southeast Asia, the Nicobarese of the Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean, and the Koreans, Japanese, and Tungusic peoples of Northeast Asia.

Besides its widespread and patchy distribution, Haplogroup O2 is also notable for the fact that it can be divided into two major subclades that show almost completely disjoint distribution. One of these subclades, Haplogroup O2a (M95), is found among some (mostly tribal) populations of South and Southeast Asia, as well as among the Khmers of Cambodia and the Balinese of Indonesia. There are also some reports that Haplogroup O2a may be associated with the so-called Negrito populations of mainland Southeast Asia, such as the Semang and the Senoi, but it is not clear whether this is their original Y-chromosome heritage or rather the result of incursion of Austroasiatic Y-chromosomes from the Khmers and related peoples who may have lent the Negritos their Austroasiatic languages in a manner similar to the Bantus' hypothesized lending of their languages and Haplogroup E Y-chromosomes to the pygmoid peoples of Africa, such as the Baka and Mbuti. The other major subclade, Haplogroup O2b (SRY465, M176), is found almost exclusively among the Koreans, the Japanese, and the Manchus.

The Northeast Asian Haplogroup O2b suggests a very interesting sort of relationship between the Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese peoples. Haplogroup O2b's parent haplogroup, Haplogroup O2*, appears to have been thinly spread throughout East Asia since prehistoric times. The derived Haplogroup O2b* (M176) is found at low frequency across the populations of the whole of Greater Manchuria, including the Tungusic, Korean, Japanese, and even the Daur people, who speak a Mongolic language that has traditionally been considered to have derived from an ancient dialect transitional between the Proto-Mongolic and Proto-Tungusic languages. One major subbranch, O2b1* (P49), is shared between the Korean and Japanese populations (with a significantly higher STR diversity among the Koreans), but its distribution does not reach the Tungusic or Daur peoples to the north. Finally, the most derived subbranch, Haplogroup O2b1a (47z), is essentially restricted to the Japanese population, although it has sporadically been detected in a few individuals who reside within the extent of the erstwhile Great Japanese Empire, in which cases it is believed to represent minor admixture from male Japanese soldiers or civilians into the local populations within the last several generations; patrilineal descent from a Japanese visitor or immigrant to some of these lands during earlier historical times is another possibility. This "nested" hierarchical and region-specific distributional pattern tends to suggest the following sequence of events:

1) The M176 mutation that defines the O2b Y-chromosome lineage first arises on an ancestral O2* chromosome belonging to a man who already resides within Greater Manchuria, or who at least already belongs to a specific "proto-Tungus-Korean" tribe.

2) Sometime after the proto-Koreans have branched off from the other populations of the Greater Manchurian region, the P49 mutation that defines Haplogroup O2b1* arises in a proto-Korean male, whose lineage becomes very successful and increases in number among the prehistoric proto-Korean population.

3) One regional subgroup of the proto-Koreans distinguishes itself from the others either culturally or by physically migrating away from their proto-Korean brethren. After the split from the greater proto-Korean population is complete, the 47z mutation that defines Haplogroup O2b1a occurs in a male of this now proto-Japanese population, who produces many male descendants and increases the frequency of the O2b1a lineage among the proto-Japanese. This very specific Haplogroup O2b1a lineage now occupies about 42.5% of the total of Haplogroup O lineages, or about 22.0% of all Y-chromosomes, among the modern Japanese, which probably reflects extreme hegemony of a certain close-knit clan in the history of the Japanese people.

In addition to suggesting a phylogenetic relationship between at least a subset of the ancestors of the Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese peoples, the distribution of Haplogroup O2b and its subbranches also argues strongly against any significant intermingling of any of these peoples during historical times.

The other major Northeast Asian Y-chromosome haplogroup, Haplogroup C3, is also found among the Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese peoples, as well as among the Mongolian peoples, Turkic peoples, and even the Ainu of Japan and the Na-Dené peoples of North America, but Haplogroup C3 displays a cline of frequency opposite to that of Haplogroup O2, to the effect that Haplogroup C3 is more frequent among the more northerly populations (Mongolian, Turkic, Northern Tungusic, Koryak, Nivkh, etc.), whereas Haplogroup O2 is more frequent among the more southerly populations (Southern Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese), and it is entirely absent from the Ainu and Na-Dené populations. The typically Sino-Tibetan and Southeast Asian Haplogroup O3 is also shared in common by most Tungusic, Mongolic, Turkic, Korean, and Japanese populations with various frequency and diversity values, which may be a genetic trace of a demic diffusion of Neolithic culture from China; however, the common occurrence at a low frequency throughout Northeast Asia of Y-chromosome Haplogroup D1 and several mtDNA haplogroups that are typical of Tibetans in addition to the Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian Haplogroup O3 may reflect some sort of relationship between the peoples of Northeast Asia and the peoples of Tibet rather than a major Neolithic or even more recent influence from China.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Haplogroup O1

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_O1_(Y-DNA)Both Haplogroup O1 and Haplogroup O3 are prototypical Chinese patrilines, and they are believed to have first evolved sometime during the late Pleistocene (Upper Paleolithic) in Southeast Asia. Both O1 and O3 are commonly found among most modern populations of China and Southeast Asia. These two lineages are also presumed to be markers of the Austronesian expansion, probably originating from prehistoric Taiwan or the neighboring southeastern coast of China, when they are found among modern populations of Maritime Southeast Asia or Oceania.[1]

By far the strongest positive correlation between Haplogroup O1 and ethnolinguistic affiliation is that which is observed between this haplogroup and the Austronesians. It is interesting that the peak frequency of Haplogroup O1 is found among the aborigines of Taiwan, precisely the region from which linguists have hypothesized that the Austronesian language family originated. A slightly weaker correlation is observed between Haplogroup O1 and the Han Chinese populations of southern China, as well as between this haplogroup and the Kradai-speaking populations of southern China and Southeast Asia. The distribution of Daic languages in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia outside of China has long been believed, for reasons of traditional linguistic geography, to reflect a recent invasion of Southeast Asia by Daic-speaking populations originating from southeastern China, and the somewhat elevated frequency of Haplogroup O1 among the Daic populations, coupled with a high frequency of Haplogroup O2a, which is a genetic characteristic of the Austro-Asiatic peoples of Southeast Asia, suggests that the genetic signature of the Daic peoples' affinity with populations of southeastern China has been weakened due to extensive assimilation of the earlier Austro-Asiatic residents of the lands which the Daic peoples invaded. Also, it has been noted that Haplogroup O1 lineages among populations of continental Southeast Asia outside of China display a reduced level of diversity when compared with populations of South China and insular Southeast Asia, which may be evidence of a bottleneck associated with the westward migration and settlement of ancestral Daic-speaking populations in Indochina.

[edit] Distribution

Haplogroup O1 is generally found wherever its brother haplogroup, Haplogroup O3, is found, although at a frequency much lower than that of Haplogroup O3. A conspicuous exception to this general pattern is presented by the Taiwanese aboriginal populations, among whom Haplogroup O1 generally dominates Haplogroup O3 in frequency. The frequency of Haplogroup O1 has been found to be negatively correlated with latitude, so that, on average, it occurs at relatively higher frequency towards the more southerly parts of its range, but it never attains majority haplogroup status outside of Taiwan. Heightened frequencies of Haplogroup O1 have also been observed in samples of populations from the Philippines and the eastern-southeastern coast of China. This haplogroup is, however, conspicuously absent from populations of the Japanese Archipelago, which seems to preclude a close genetic relationship between the peoples of Japan and the Austronesians, despite many enthusiastic attempts to prove a common origin of the Japanese and Austronesian languages. Haplogroup O1a-M119 Y-chromosomes have also been found to occur at low frequency among various populations of Siberia, such as the Nivkhs (one of 17 sampled Y-chromosomes), Ulchi/Nanai (2/53), Yenisey Evenks (1/31), and especially the Buryats living in the Sayan-Baikal uplands of Irkutsk Oblast (6/13).[2]

[edit] Frequencies

The frequencies of Haplogroup O1 among various East Asian and Austronesian populations suggest a complex genetic history of the modern Han populations of southern China. Although Haplogroup O1 occurs only at an average frequency of approximately 4% among Han populations of northern China and peoples of southwestern China and Southeast Asia who speak Tibeto-Burman languages, the frequency of this haplogroup among the Han populations of southern China nearly quadruples to about 15%. It is particularly interesting that the frequency of Haplogroup O1 among the Southern Han has been found to be slightly greater than the arithmetic mean of the frequencies of Haplogroup O1 among the Northern Han and a pooled sample of Austronesian populations. This suggests that modern Southern Han populations possess a non-trivial number of male ancestors who were originally affiliated with some Austronesian-related culture, or who at least shared a genetic affinity with many of the ancestors of modern Austronesian peoples.

Subgroups

The subclades of Haplogroup O1 with their defining mutation, according to the 2006 ISOGG tree:

- O1 (MSY2.2)

- O1*

- O1a (M119) Typical of Austronesians, southern Han Chinese, and Tai-Kadai peoples

- O1a*

- O1a1 (M101)

- O1a2 (M50, M103, M110) Occurs among Austronesian peoples of Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Madagascar as well as among some populations of continental Southeast Asia

[edit] References

- ^ Karafet et al. (February 2005), "Balinese Y-Chromosome Perspective on the Peopling of Indonesia: Genetic Contributions from Pre-Neolithic Hunter-Gatherers, Austronesian Farmers, and Indian Traders", Human Biology, 77: 93-114.

- ^ The Dual Origin and Siberian Affinities of Native American Y Chromosomes, Jeffrey T. Lell, Rem I. Sukernik, Yelena B. Starikovskaya, Bing Su, Li Jin, Theodore G. Schurr, Peter A. Underhill, and Douglas C. Wallace, American Journal of Human Genetics 70:192-206, 2002

3. Li et al. (2007) Y chromosomes of Prehistoric People along the Yangtze River[1]. Hum Genet 122:383-388.

4. Li et al. (2008) Paternal Genetic Affinity between Western Austronesians and Daic Populations[2]. BMC Evol Biol 8:146.

5. Li et al. (2008) Paternal Genetic Structure of Hainan Aborigines Isolated at the Entrance to East Asia[3]. PLoS ONE 3(5):e2168.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Haplogroup O3 (Y-DNA)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_O3_(Y-DNA)Origins

Origins

Haplogroup O3 is a descendant haplogroup of haplogroup O. Some researchers believe that it first appeared in China approximately 10,000 years ago. However, others believe that the high internal diversity of Haplogroup O3 indicates a Late Pleistocene (Upper Paleolithic) origin in South China or Southeast Asia of the M122 mutation that defines the entire O3 clade, while the common presence among a wide variety of modern East and Southeast Asian nations of closely related haplotypes belonging to certain subclades of Haplogroup O3 is considered to point to a recent (e.g., Holocene) geographic dispersion of a certain subset of the ancient variation within Haplogroup O3. The spread of these particular subsets of Haplogroup O3 is conjectured to be closely associated with the sudden agricultural boom associated with rice farming.

The prehistoric peopling of East Asia by modern humans remains controversial with respect to early population migrations. In a systematic sampling and genetic screening of an East Asian–specific Y-chromosome haplogroup (O3-M122) in 2,332 individuals from diverse East Asian populations. Results indicate that the O3-M122 lineage is dominant in East Asian populations, with an average frequency of 44.3%. The microsatellite data show that the O3-M122 haplotypes in southern East Asia are more diverse than those in northern East Asia, suggesting a southern origin of the O3-M122 mutation. It was estimated that the early northward migration of the O3-M122 lineages in East Asia occurred ~25,000–30,000 years ago, consistent with the fossil records of modern humans in East Asia. [1]

[edit] Distribution

Although Haplogroup O3 appears to be primarily associated with Chinese populations, it also forms a significant component of the Y-chromosome diversity of most modern populations of the East Asian region. Haplogroup O3 is found in over 50% of all modern Chinese males (ranging up to over 80% in certain regional subgroups of the Han ethnicity), about 40% of Manchurian, Korean, and Vietnamese males, about 33.3%[2] to 60.7%[3] of Filipino males, about 35% of Malaysian males, about 25% of Zhuang[4] and Indonesian[5] males, and about 15%[6] to 20%[2] of Japanese males. The distribution of Haplogroup O3 stretches far into Central Asia (approx. 30% of Salar, 24% of Dongxiang[7], 18% to 22.8% of Mongolians, 12% of Uyghurs, 9% of Kazakhs, 6.2% of Altayans[8], and 4.1% of Uzbeks) and Oceania (approx. 25% of Polynesians, 18% of Micronesians, and 5% of Melanesians[9]), albeit with reduced frequencies of most subclades. It should be noted that Haplogroup O3* Y-chromosomes, which are not defined by any identified downstream markers, are actually more common among certain non-Han Chinese populations than among Han Chinese ones, and the presence of these O3* Y-chromosomes among various populations of Central Asia, East Asia, and Oceania is more likely to reflect a very ancient shared ancestry of these populations rather than the result of any historical events. It remains to be seen whether Haplogroup O3* Y-chromosomes can be parsed into distinct subclades that display significant geographical or ethnic correlations.

Among all the populations of East and Southeast Asia, Haplogroup O3 is most closely associated with those that speak a Sinitic, Tibeto-Burman, or Hmong-Mien language. Haplogroup O3 comprises about 50% or more of the total Y-chromosome variation among the populations of each of these language families. The Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman language families are generally believed to be derived from a common Sino-Tibetan protolanguage, and most linguists place the homeland of the Sino-Tibetan language family somewhere in northern China. The Hmong-Mien languages and cultures, for various archaeological and ethnohistorical reasons, are also generally believed to have derived from a source somewhere north of their current distribution, perhaps in northern or central China. The Tibetans, however, despite the fact that they speak a language of the Tibeto-Burman language family, have high percentages of the otherwise rare haplogroups D1 and D3, which are also found at much lower frequencies among the members of some other ethnic groups in East Asia and Central Asia.

Haplogroup O3 has been implicated as a diagnostic genetic marker of the Austronesian expansion when it is found in populations of Oceania. Its distribution in Oceania is mostly limited to the traditionally Austronesian culture zones, including moderately high frequencies in the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Polynesia, with generally lower frequencies found in coastal and island Melanesia, Micronesia, and Taiwanese aboriginal tribes.

The subgroup O3a5-M134 is particularly closely associated with Sino-Tibetan populations, and it is generally not found outside of areas where a Sino-Tibetan language is currently spoken or that are historically supposed to have undergone Chinese colonization or immigration, such as Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. However, its presence among non-Sino-Tibetan populations is always very limited and never amounts to more than 10% of the total Y-chromosome diversity. There are also reports that Y-chromosomes belonging to Haplogroup O3a5 have been sampled from populations of such far-flung places as Western Samoa. Surprisingly, Haplogroup O3a5-M134 Y-chromosomes have also been found in about 1% to 3% of indigenous Australian men in the northwest of that continent, which might indicate that a certain degree of contact has occurred between the Austronesian expansion from Asia and some indigenous Australian populations. The fact that Haplogroup O3a5 is so strongly associated with Chinese populations, however, and the fact that no Y-chromosome haplogroups characteristic of Austronesian populations have been found among these indigenous Australian populations may be taken to suggest the possibility of some direct Chinese-Australian contact in the precolonial era. Within Japan, the subgroup O3a5-M134 forms the majority of the haplogroup O3 Y-chromosomes detected.

Haplogroup O3's brother clade, Haplogroup O1, displays a similar geographical distribution, being found among nearly all the populations of East and Southeast Asia, but generally at a frequency much lower than that of Haplogroup O3. Another brother clade, Haplogroup O2, has an impressive extent of dispersal, as it is found among the males of populations as widely separated as the Kolarians of India and the Japanese of Japan; however, Haplogroup O2's distribution is much more patchy, and the Haplogroup O2 Y-chromosomes found among the Mundas and the Japanese belong to distinct subclades.

[edit] References

1. ^ Hong Shi, Yong-li Dong, Bo Wen, Chun-Jie Xiao, Peter A. Underhill, Pei-dong Shen, Ranajit Chakraborty, Li Jin, and Bing Su, "Y-Chromosome Evidence of Southern Origin of the East Asian–Specific Haplogroup O3-M122" American Journal of Human Genetics 77:408–419, 2005 (HTML) (PDF)

2. ^ a b Dual origins of the Japanese: common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes, Michael F. Hammer et al., Journal of Human Genetics (Jan. 2006)

3. ^ Matthew E. Hurles, Bryan C. Sykes, Mark A. Jobling, and Peter Forster, "The Dual Origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: Evidence from Maternal and Paternal Lineages," American Journal of Human Genetics 76:894–901, 2005.

4. ^ Chen Jing, Li Hui et al., "Y-chromosome Genotyping and Genetic Structure of Zhuang Populations," Acta Genetica Sinica (Dec. 2006)

5. ^ Hui Li, Bo Wen, Shu-Juo Chen, Bing Su, Patcharin Pramoonjago, Yangfan Liu, Shangling Pan, Zhendong Qin, Wenhong Liu, Xu Cheng, Ningning Yang, Xin Li, Dinhbinh Tran, Daru Lu, Mu-Tsu Hsu, Ranjan Deka, Sangkot Marzuki, Chia-Chen Tan and Li Jin, "Paternal genetic affinity between western Austronesians and Daic populations," BMC Evolutionary Biology 2008, 8:146 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-146. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/8/146

6. ^ Y-chromosomal Binary Haplogroups in the Japanese Population and their Relationship to 16 Y-STR Polymorphisms, I. Nonaka et al., Annals of Human Genetics (Feb. 2007)

7. ^ Wei Wang, Cheryl Wise, Tom Baric, Michael L. Black and Alan H. Bittles, "The origins and genetic structure of three co-resident Chinese Muslim populations: the Salar, Bo'an and Dongxiang," Human Genetics (2003)

8. ^ V. N. Kharkov, V. A. Stepanov, O. F. Medvedeva, M. G. Spiridonova, M. I. Voevoda, V. N. Tadinova and V. P. Puzyrev, "Gene pool differences between Northern and Southern Altaians inferred from the data on Y-chromosomal haplogroups," Russian Journal of Genetics, Volume 43, Number 5 (May, 2007)

9. ^ Balinese Y-Chromosome Perspective on the Peopling of Indonesia: Genetic Contributions from Pre-Neolithic Hunter-Gatherers, Austronesian Farmers, and Indian Traders, Tatiana M. Karafet, J. S. Lansing, Alan J. Redd, Joseph C. Watkins, S. P. K. Surata, W. A. Arthawiguna, Laura Mayer, Michael Bamshad, Lynn B. Jorde, and Michael F. Hammer, Human Biology (Feb. 2005)

9. Gan Rui-Jing, Pan Shang-Ling, Mustavich Laura F, Qin Zhen-Dong, Cai Xiao-Yun, Qian Ji, Liu Cheng-Wu, Peng Jun-Hua, Li Shi-Lin, Xu Jie-Shun, Jin Li, Li Hui*: the Genographic Consortium (2008) Pinghua Population as an Exception of Han Chinese's Coherent Genetic Structure [1]. J Hum Genet 53:303-313.

Truth

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O2b

The phylogeography of Haplogroup O2b suggests a very ancient origin in Manchuria, followed by a long period of isolated evolution and population increase within the Korean Peninsula.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_O2_(Y-DNA)

Haplogroup O2 is also notable for the fact that it can be divided into two major subclades that show almost completely disjoint distribution.

1: One of these subclades, Haplogroup O2a (M95), is found among some (mostly tribal) populations of South and Southeast Asia, as well as among the Khmers of Cambodia and the Balinese of Indonesia. There are also some reports that Haplogroup O2a may be associated with the so-called Negrito populations of mainland Southeast Asia, such as the Semang and the Senoi, but it is not clear whether this is their original Y-chromosome heritage or rather the result of incursion of Austroasiatic Y-chromosomes from the Khmers and related peoples who may have lent the Negritos their Austroasiatic languages in a manner similar to the Bantus' hypothesized lending of their languages and Haplogroup E Y-chromosomes to the pygmoid peoples of Africa, such as the Baka and Mbuti.

2: The other major subclade, Haplogroup O2b (SRY465, M176), is found almost exclusively among the

Koreans, the Japanese, and the Manchus.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_K_(Y-DNA)

Haplogroup K (Y-DNA)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Haplogroup K | |

| Time of origin | 35,000-40,000 years BP |

| Place of origin | Southwest Asia |

| Ancestor | IJK |

| Descendants | L, M, NOP, S and T |

|---|---|

| Defining mutations | M9 |

In human genetics, Haplogroup K (M9) is a Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. This haplogroup is a descendant of Haplogroup IJK. Its major descendant haplogroups are L (M20), M (P256), NO (M214) (plus NO's descendants N and O), P (M45) (plus P's descendants Q and R), S (M230), and T (M70). Haplogroups K1, K2, K3 and K4 are found only at low frequency in South Asia, the Malay Archipelago, Oceania, and Australia.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Origins

Y-DNA haplogroup K is an old lineage established approximately 40,000 thousand years ago whose origins were probably in southwestern Asia. At present this group contains two distinct classes of subgroups: (1) major groups L to T (refer to the main tree at Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree) and (2) minor groups K* and K1 to K4 which do not have any of the SNPs defining the major groups. These groups are found at low frequencies in various parts of Africa, Eurasia, Australia and the South Pacific.[1]

[edit] Subgroups

The subclades of Haplogroup K with their defining mutation, according to Karafet et al (2008) [2] (abbreviated for clarity to a maximum of five steps away from the root of Haplogroup K):

Note The 2008 paper made a number of changes compared to the previous 2006 ISOGG tree. The former subgroups K2 and K5 were renamed Haplogroups T and S; the old subgroups K1 and K7 were re-assigned as new subgroups M2 and M3 of a redefined Haplogroup M; and the former subgroups K3, K4 and K6 were renamed to new K1, K2 and K3.

- K (M9) Typical of populations of northern Eurasia, eastern Eurasia, Melanesia, and the Americas, with a moderate distribution throughout Southwest Asia, northern Africa, and Oceania

- K*

- K1 (M147) Found at low frequencies in South Asia

- K2 (P60)

- K3 (P79) Found in Melanesia

- K4 (P261, P263)

- L (M11, M20, M22, M61, M185, M295) Typical of populations of Pakistan

- L*

- L1 (M27, M76) Typical of Indians and Sri Lankans, with a moderate distribution among Indo-Iranian populations of South Asia

- L2 (M317) Found at low frequency in Central Asia, Southwest Asia, and Southern Europe

- L2*

- L2a (M274)

- L2b (M349)

- L3 (M357) Found frequently among Burusho and Pashtuns, with a moderate distribution among the general Pakistani population

- L3*

- L3a (PK3) Found among Kalash

- M (P256)

- M1 (M4, M5, M106, M186, M189, P35) Typical of Papuan peoples

- M1*

- M1a (P34)

- M1a*

- M1a1 (P51)

- M1b (P87)

- M1b*

- M1b1 (M104 (P22)) Typical of populations of the Bismarck Archipelago and Bougainville Island[1]

- M1b1*

- M1b1a (M16)

- M1b1b (M83)

- M2 (M353, M387) Found at a low frequency in the Solomon Islands and Fiji

- M2*

- M2a (SRY9138 (M177))

- M3 (P117) Found in Melanesia

- M1 (M4, M5, M106, M186, M189, P35) Typical of Papuan peoples

- NO (M214)

- NO*

- N (M231)

- N*

- N1 (LLY22g)

- N1a (M128) Found at a low frequency among Manchu, Sibe, Manchurian Evenks, Koreans, northern Han Chinese, Buyei, and some Turkic peoples of Central Asia

- N1b (P43) Typical of Northern Samoyedic peoples; also found at low to moderate frequency among some other Uralic peoples, Turkic peoples, Mongolic peoples, Tungusic peoples, and Siberian Yupiks

- N1b*

- N1b1 (P63)

- N1c (Tat (M46), P105) Typical of the Sakha and Uralic peoples, with a moderate distribution throughout North Eurasia

- N1c*

- N1c1 (M178)

- N1c1*

- N1c1a (P21)

- N1c1b (P67)

- N1c1c (P119)

- O (M175)

- O*

- O1 (MSY2.2) Typical of Austronesians, southern Han Chinese, and Kradai peoples

- O1*

- O1a (M119)

- O1a*

- O1a1 (M101)

- O1a2 (M50, M103, M110)

- O2 (P31, M268)

- O2*

- O2a (M95) Typical of Austro-Asiatic peoples, Kradai peoples, Malays, Indonesians, and Malagasy, with a moderate distribution throughout South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Central Asia

- O2a*

- O2a1 (M88, M111)

- O2a2 (M297)

- O2b (M176/SRY465, P49, 022454)

- O2b* Typical of Koreans, with a moderate distribution among populations of Indonesia, Japan, Manchuria, Micronesia, Thailand, and Vietnam

- O2b1 (47z) Typical of Japanese and Ryukyuans, with a moderate distribution among Indonesians, Thais, Koreans, and Vietnamese

- O3 (M122) Typical of populations of East Asia, Southeast Asia, and culturally Austronesian regions of Oceania, with a moderate distribution in Central Asia

- O3*

- O3a (M324, P93, P197, P198, P199, P200)

- O3a*

- O3a1 (DYS257/P27.2, M121)

- O3a2 (M164)

- O3a3 (P201/021354)

- O3a3*

- O3a3a (M159)

- O3a3b (M7) Typical of Hmong-Mien peoples, with a moderate distribution among Han Chinese, Buyei, Qiang, and Oroqen[2]

- O3a3c (M134) Typical of Sino-Tibetan peoples, with a moderate distribution throughout East Asia and Southeast Asia

- O3a4 (002611)

- O3a4*

- O3a4a (P103)

- O3a5 (M300)

- O3a6 (M333)

- P (92R7, M45, M74, (N12), P27)

- P*

- Q (M242)

- Q*

- Q1 (P36.2)

- Q1*

- Q1a (MEH2)

- Q1a*

- Q1a1 (M120, M265/N14) Found at low frequency among Chinese, Koreans, Dungans, and Hazara[3][4]

- Q1a2 (M25, M143) Found at low to moderate frequency among some populations of Southwest Asia, Central Asia, and Siberia

- Q1a3 (M346)

- Q1a3* Found at low frequency in Pakistan and India

- Q1a3a (M3) Typical of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Q1a3a*

- Q1a3a1 (M19) Found among some indigenous peoples of South America, such as the Ticuna and the Wayuu[5]

- Q1a3a2 (M194)

- Q1a3a3 (M199, P106, P292)

- Q1a4 (P48)

- Q1a5 (P89)

- Q1a6 (M323) Found in a significant minority of Yemeni Jews

- Q1b (M378) Found at low frequency among samples of Hazara and Sindhis

- R (M207 (UTY2), M306 (S1), S4, S8, S9)

- R*

- R1 (M173)

- R1*

- R1a (SRY10831.2 (SRY1532))

- R1a*

- R1a1 (M17, M198) Typical of populations of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia, with a moderate distribution throughout Western Europe, Southwest Asia, and southern Siberia

- R1b (M343) Typical of populations of Western Europe, with a moderate distribution throughout Eurasia and in parts of Africa

- R1b*

- R1b1 (P25)

- R2 (M124) Typical of populations of South Asia, with a moderate distribution in Central Asia and the Caucasus

- S (M230) Typical of populations of the highlands of New Guinea; also found at lower frequencies in adjacent parts of Indonesia and Melanesia

- S*

- S1 (M254)

- S1*

- S1a (M226)

- T (M70, M184, M193, M272) Found in a significant minority of Somalis, Ethiopians, Fulbe, Egyptians, Omani & Serbian people; also found at low frequency throughout the Mediterranean and parts of India

- T*

- T1 (M320)

[edit] References

- ^ Laura Scheinfeldt, Françoise Friedlaender, Jonathan Friedlaender, Krista Latham, George Koki, Tatyana Karafet, Michael Hammer and Joseph Lorenz, "Unexpected NRY Chromosome Variation in Northern Island Melanesia," Molecular Biology and Evolution 2006 23(8):1628-1641

- ^ Yali Xue, Tatiana Zerjal, Weidong Bao, Suling Zhu, Qunfang Shu, Jiujin Xu, Ruofu Du, Songbin Fu, Pu Li, Matthew E. Hurles, Huanming Yang, and Chris Tyler-Smith, "Male Demography in East Asia: A North–South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times," Genetics 2006 April; 172(4): 2431–2439.

- ^ Supplementary Table 2: NRY haplogroup distribution in Han populations, from the online supplementary material for the article by Bo Wen et al., "Genetic evidence supports demic diffusion of Han culture," Nature 431, 302-305 (16 September 2004)

- ^ Table 1: Y-chromosome haplotype frequencies in 49 Eurasian populations, listed according to geographic region, from the article by R. Spencer Wells et al., "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 28, 2001)

- ^ "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas," Maria-Catira Bortolini et al., American Journal of Human Genetics 73:524-539, 2003

- O (M175)

- O*

- O1 (MSY2.2) Typical of Austronesians, southern Han Chinese, and Kradai peoples

- O1*

- O1a (M119)

- O1a*

- O1a1 (M101)

- O1a2 (M50, M103, M110)

- O2 (P31, M268)

- O2*

- O2a (M95) Typical of Austro-Asiatic peoples, Kradai peoples, Malays, Indonesians, and Malagasy, with a moderate distribution throughout South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Central Asia

- O2a*

- O2a1 (M88, M111)

- O2a2 (M297)

- O2b (M176/SRY465, P49, 022454)

- O2b* Typical of Koreans, with a moderate distribution among populations of Indonesia, Japan, Manchuria, Micronesia, Thailand, and Vietnam

- O2b1 (47z) Typical of Japanese and Ryukyuans, with a moderate distribution among Indonesians, Thais, Koreans, and Vietnamese

- O3 (M122) Typical of populations of East Asia, Southeast Asia, and culturally Austronesian regions of Oceania, with a moderate distribution in Central Asia

- O3*

- O3a (M324, P93, P197, P198, P199, P200)

- O3a*

- O3a1 (DYS257/P27.2, M121)

- O3a2 (M164)

- O3a3 (P201/021354)

- O3a3*

- O3a3a (M159)

- O3a3b (M7) Typical of Hmong-Mien peoples, with a moderate distribution among Han Chinese, Buyei, Qiang, and Oroqen[2]

- O3a3c (M134) Typical of Sino-Tibetan peoples, with a moderate distribution throughout East Asia and Southeast Asia

- O3a4 (002611)

- O3a4*

- O3a4a (P103)

- O3a5 (M300)

- O3a6 (M333)

http://www.imbice.org.ar/es/lab_06_b/06.pdf

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://pritch.bsd.uchicago.edu/publications/FalushEtAl03_Science.pdf

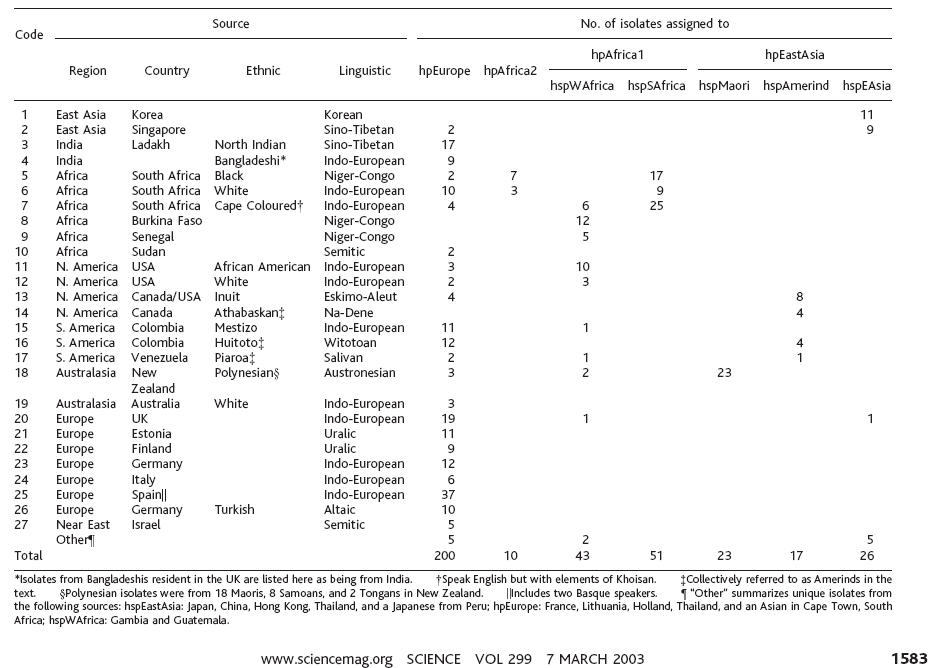

Daniel Falush, Thierry Wirth, Bodo Linz, Jonathan K. Pritchard, Matthew Stephens, Mark Kidd, Martin J. Blaser, David Y. Graham, Sylvie Vacher, Guillermo I. Perez-Perez, Yoshio Yamaoka, Francis Mégraud, Kristina Otto, Ulrike Reichard, Elena Katzowitsch, Xiaoyan Wang, Mark Achtman, and Sebastian Suerbaum

Science 7 March 2003; 299: 1582-1585

Jared Diamond and Peter Bellwood

Science 25 April 2003; 300: 597-603

-------------------------------------------

According to the latest 2007 genetic/DNA study by Jiang Ya-ping at Labs of Cellular and Molecular Evolution in Kunming Institute of Zoology, China,

the , contradicting the theory of "Beijing Apes"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altaic_languages

Altaic languages

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Altaic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | East, North, Central, and West Asia and Eastern Europe |

| Genetic classification: | Altaic |

| Subdivisions: | Japonic (usually included) |

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | tut |

Altaic is a disputed language family that is generally held by its proponents to include the Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Korean, and Japonic language families (Georg et al. 1999:73-74).[1] These languages are spoken in a wide arc stretching from northeast Asia through Central Asia to Anatolia and eastern Europe (Turks, Kalmyks).[2] The group is named after the Altai Mountains, a mountain range in Central Asia.

These language families share numerous characteristics. The debate is over the origin of their similarities. One camp, often called the "Altaicists", views these similarities as arising from common descent from a Proto-Altaic language spoken several thousand years ago. The other camp, often called the "anti-Altaicists", views these similarities as arising from areal interaction between the language groups concerned. Some linguists believe the case for either interpretation is about equally strong; they have been called the "skeptics" (Georg et al. 1999:81).

Another view accepts Altaic as a valid family but includes in it only Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic. This view was widespread prior to the 1960s, but has almost no supporters among specialists today (Georg et al. 1999:73-74). The expanded grouping, including Korean and, from the early 1970s on, Japanese, came to be known as "Macro-Altaic", leading to the designation by back-formation of the smaller grouping as "Micro-Altaic". A minority of Altaicists continues to support the inclusion of Korean but not that of Japanese (Poppe 1976:470, Georg et al. 1999:65, 74).

Micro-Altaic would include about 66 living languages,[3] to which Macro-Altaic would add Korean, Japanese, and the Ryukyuan languages for a total of about 74. (These are estimates, depending on what is considered a language and what is considered a dialect. They do not include earlier states of language, such as Old Japanese.) Micro-Altaic would have a total of about 348 million speakers today, Macro-Altaic about 558 million.

The history of the Altaic idea is detailed below, as well as the case against it.

Contents

[hide]- 1 History of the Altaic idea

- 2 A language family or a Sprachbund?

- 3 Postulated Urheimat

- 4 List of Altaicists and critics of Altaic

- 5 Comparative grammar of the proposed Altaic language family

- 6 Modern peoples

- 7 Bibliography

- 8 See also

- 9 External links

Works cited

- Aalto, Pentti. 1955. "On the Altaic initial *p-." Central Asiatic Journal 1, 9–16.

- Anthony, David W. 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Blažek, Václav. 2006. "Current progress in Altaic etymology." Linguistica Online, 30 January 2006.

- Boller, Anton. 1857. Nachweis, daß das Japanische zum ural-altaischen Stamme gehört. Wien.

- Clauson, Gerard. 1956. "The case against the Altaic theory." Central Asiatic Journal 2, 181–187.

- Clauson, Gerard. 1959. "The case for the Altaic theory examined." Akten des vierundzwanzigsten internationalen Orientalisten-Kongresses, edited by H. Franke. Wiesbaden: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft, in Komission bei Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Clauson, Gerard. 1968. "A lexicostatistical appraisal of the Altaic theory." Central Asiatic Journal 13: 1-23.

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1963. "Bemerkungen zur Verwandtschaft der sog. altaische Sprachen", 'Remarks on the relationship of the so-called Altaic languages'. In Gerhard Doerfer, Türkische und mongolische Elemente im Neupersischen, Bd. I: Mongolische Elemente im Neupersischen, 1963, 51–105. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1973. "Lautgesetze und Zufall: Betrachtungen zum Omnicomparativismus." Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 10.

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1974. "Ist das Japanische mit den altaischen Sprachen verwandt?" Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 114.1.

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1985. Mongolica-Tungusica. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1988. Grundwort und Sprachmischung: Eine Untersuchung an Hand von Körperteilbezeichnungen. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Dybo, Anna V. and Georgiy S. Starostin. 2008. "In defense of the comparative method, or the end of the Vovin controversy." Aspects of Comparative Linguistics 3, 109–258. Moscow: RSUH Publishers.

- Georg, Stefan, Peter A. Michalove, Alexis Manaster Ramer, and Paul J. Sidwell. 1999. "Telling general linguists about Altaic." Journal of Linguistics 35:65-98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Georg, Stefan. 1999 / 2000. "Haupt und Glieder der altaischen Hypothese: die Körperteilbezeichnungen im Türkischen, Mongolischen und Tungusischen" ('Head and members of the Altaic hypothesis: The body-part designations in Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic'). Ural-altaische Jahrbücher, neue Folge B 16, 143–182.

- Georg, Stefan. 2004. Review of Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Diachronica 21.2, 445-450.

- Georg, Stefan. 2005. "Reply [to Starostin 2005]." Diachronica 22.2, 455–457.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 2000–2002. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, 2 volumes. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Manaster Ramer, Alexis and Paul Sidwell. 1997. "The truth about Strahlenberg's classification of the languages of Northeastern Eurasia." Journal de la Société finno-ougrienne 87, 139–160.

- Menges, Karl. H. 1975. Altajische Studien II. Japanisch und Altajisch. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Mallory, J.P. 1989. In Search of the Indo-Europeans. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1971. Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226527190.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1980. Origins of the Japanese Language: Lectures in Japan during the Academic Year 1977–78. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295957662.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1986. Nihongo: In Defence of Japanese. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 0485112515.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1991. "Genetic connections among the Altaic languages." In Sydney M. Lamb and E. Douglas Mitchell (editors), Sprung from Some Common Source: Investigations into the Prehistory of Languages, 1991, 293–327. ISBN 0804718970.

- Miller, Roy Andrew. 1996. Languages and History: Japanese, Korean and Altaic. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. ISBN 9748299694.

- Patrie, James. 1982. The Genetic Relationship of the Ainu Language. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824807243.

- Poppe, Nicholas. 1960. Vergleichende Grammatik der altaischen Sprachen. Teil I. Vergleichende Lautlehre, 'Comparative Grammar of the Altaic Languages, Part 1: Comparative Phonology'. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. (Only part to appear of a projected larger work.)

- Poppe, Nicholas. 1965. Introduction to Altaic Linguistics. Ural-altaische Bibliothek 14. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Poppe, Nicholas. 1976. Review of Karl H. Menges, Altajische Studien II. Japanisch und Altajisch (1975). In The Journal of Japanese Studies 2.2, 470–474.

- Ramstedt, G.J. 1952. Einführung in die altaische Sprachwissenschaft II. Formenlehre, 'Introduction to Altaic Linguistics, Volume 2: Morphology', edited and published by Pentti Aalto. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Ramstedt, G.J. 1957. Einführung in die altaische Sprachwissenschaft I. Lautlehre, 'Introduction to Altaic Linguistics, Volume 1: Phonology', edited and published by Pentti Aalto. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Ramstedt, G.J. 1966. Einführung in die altaische Sprachwissenschaft III. Register, 'Introduction to Altaic Linguistics, Volume 3: Index', edited and published by Pentti Aalto. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Robbeets, Martine. 2005. Is Japanese related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic? Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Robbeets, Martine. 2007. "How the actional suffix chain connects Japanese to Altaic." In Turkic Languages 11.1, 3–58.

- Schönig, Claus. 2003. "Turko-Mongolic Relations." In The Mongolic Languages, edited by Juha Janhunen, 403–419. London: Routledge.

- Starostin, Sergei A. 1991. Altajskaja problema i proisxoždenie japonskogo jazyka, 'The Altaic Problem and the Origin of the Japanese Language'. Moscow: Nauka.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak. 2003. Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages, 3 volumes. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9004131531.

- Starostin, Sergei A. 2005. "Response to Stefan Georg's review of the Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages." Diachronica 22(2), 451–454.

- Strahlenberg, P.J.T. von. 1730. Das nord- und ostliche Theil von Europa und Asia.... Stockholm. (Reprint: 1975. Studia Uralo-Altaica. Szeged and Amsterdam.)

- Strahlenberg, P.J.T. von. 1738. Russia, Siberia and Great Tartary, an Historico-geographical Description of the North and Eastern Parts of Europe and Asia.... (Reprint: 1970. New York: Arno Press.) English translation of the previous.

- Street, John C. 1962. Review of N. Poppe, Vergleichende Grammatik der altaischen Sprachen, Teil I (1960). Language 38, 92–98.

- Tekin, Talat. 1994. "Altaic languages." In The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, Vol. 1, edited by R.E. Asher. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press.

- Unger, J. Marshall. 1990. "Summary report of the Altaic panel." In Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology, edited by Philip Baldi, 479–482. Berlin - New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Vovin, Alexander. 1993. "About the phonetic value of the Middle Korean grapheme ᅀ." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 56(2), 247–259.

- Vovin, Alexander. 1994. "Genetic affiliation of Japanese and methodology of linguistic comparison." Journal de la Société finno-ougrienne 85, 241–256.

- Vovin, Alexander. 2001. "Japanese, Korean, and Tungusic: evidence for genetic relationship from verbal morphology." Altaic Affinities (Proceedings of the 40th Meeting of PIAC, Provo, Utah, 1997), edited by David B. Honey and David C. Wright, 83–202. Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies.

- Vovin, Alexander. 2005. "The end of the Altaic controversy" (review of Starostin et al. 2003). Central Asiatic Journal 49.1, 71–132.

- Whitney Coolidge, Jennifer. 2005. Southern Turkmenistan in the Neolithic: A Petrographic Case Study. Oxbow Books.

- 이기문, 국어사 개설, 탑출판사, 1991.

[edit] Further reading

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1997. "Does Altaic exist?" In Irén Hegedus, Peter A. Michalove, and Alexis Manaster Ramer (editors), Indo-European, Nostratic and Beyond: A Festschrift for Vitaly V. Shevoroshkin, Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man, 1997, 88–93. (Reprinted in Joseph H. Greenberg, Genetic Linguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, 325–330.)

- Hahn, Reinhard F. 1994. LINGUIST List 5.908, 18 Aug 1994.

- Janhunen, Juha. 1992. "Das Japanische in vergleichender Sicht." Journal de la Société finno-ougrienne 84, 145-61.

- Johanson, Lars. 1999. "Cognates and copies in Altaic verb derivation." Language and Literature – Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages: Studies in Honour of Roy Andrew Miller on His 75th Birthday, edited by Karl H. Menges and Nelly Naumann, 1-13. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. (Also: HTML version.)

- Johanson, Lars. 1999. "Attractiveness and relatedness: Notes on Turkic language contacts." Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special Session on Caucasian, Dravidian, and Turkic Linguistics, edited by Jeff Good and Alan C.L. Yu, 87-94. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Johanson, Lars. 2002. Structural Factors in Turkic Language Contacts, translated by Vanessa Karam. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press.

- Kortlandt, Frederik. 1993. "The origin of the Japanese and Korean accent systems." Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 26, 57–65.

- Martin, Samuel E. 1966. "Lexical evidence relating Korean to Japanese." Language 12.2, 185–251.

- Nichols, Johanna. 1992. Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Robbeets, Martine. 2004. "Belief or argument? The classification of the Japanese language." Eurasia Newsletter 8. Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. 1987. A Guide to the World's Languages. Stanford University Press.

- Sinor, Denis. 1990. Essays in Comparative Altaic Linguistics. Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. ISBN 0933070268.

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

- Altaic family tree Ethnologue (Micro-Altaic)

- Monumenta altaica Altaic linguistics website, maintained by Ilya Gruntov

- Altaic Etymological Dictionary, database version by Sergei A. Starostin, Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak (does not include introductory chapters)

- LINGUIST List 5.911 defense of Altaic by Alexis Manaster Ramer (1994)

- LINGUIST List 5.926 1. Remarks by Alexander Vovin. 2. Clarification by J. Marshall Unger. (1994)

http://www.africaresource.com/rasta/sesostris-the-great-the-egyptian-hercules/african-roots-of-china/

African Roots Of China

Africans launched Chinese civilisation

By Nsaka Sesepkekiu

Student of African and Asian Studies

Faculty of Humanities

University of the West Indies

Trinidad and Tobago

Whenever we hear the term “Chinese” we often associate the word with short slanted eyed people who can fight kung fu. With the recent celebration of establishment of the People’s Republic of China, I wish not only to congratulate them but also to add some insight into their history.

The original, first, native, primitive inhabitants of China were black Africans who arrived there about 100,000 years ago and dominated the region until a few thousand years ago when the Mongol advance into that region began. These Africans who fled the Mongol onslaught can still be found in South East Asia and the Pacific Islands misnomered Nigritos or “small black men.” The Agta of the Philippines is one such example. Indeed archeology, forensic and otherwise confirm that China’s first two dynasties, the Xia and the Ch’ang/Sh’ang, were largely Black African with an Australoid, called “Madras Indian” or “Chamar” in Trinidad, present in small percentages. These Africans would carry an art of fighting developed in the Horn of Africa into China which today we call martial arts: Tai Chi, Kung fu and Tae Kwon Do. Even the oracle of the I-Ching came with a later African group, the Akkadians of Babylon.

Around 500 BCE an African living in India called Gautama would establish a religion called Buddhism which would come to dominate Chinese thought. Any one who is in doubt should consult Geoffrey Higgins’s Anacalypsis, Albert Churchward’s Origin and development of Religions, Gerald Massey’s Egypt the Light of the World, Riunoko Rashidi’s African Presence in Early Asia and J A Roger’s Sex and Race Vol 1. Many Africans survived the Mongol invasion into the twentieth century only to be exterminated by Chairman Mao’s programme of Cultural cleansing. Under this programme millions of Africans and Afro-Asians were killed from 1951-1956. Contribute we still did, giving the People’s Republic of China its first Chief Minister in the name of Eugene Chen, a Trinidadian of George Street, Port-of-Spain, who was of an African mother and a Chinese father.

For further reading on this individual one should consult J A Rogers’ World’s Great Men of Colour Vol I. So next time the word China or Chinese is mentioned remember that Africans played a pivotal role in launching what is called Chinese civilisation, if such a thing exists.

Â

http://www.raceandhistory.com/

Â

You are reading Rasta Livewire. For all things Africa, visit AfricaResource: The Place for Africa on the Net.

Related Posts:

- Ancient Black Chinese From East Africa -- (by Prof Jin Li)

- The Black African Foundation of China: The First Chinese

- Africa/China Co-operation: 50 Year Review

- Nigerian Satellite launched by China

- China To Build Nigerian Railway

- The Forgotten People:The African Origin Of China Part 1 - By: Lauren K. Clark

- Africa Makes A Splash in Beijing

- Human Diversity: Pale Skin/Black Genes

- The Black African Foundation of China -- Honouring The Aboriginal Black People of China

The Black African Foundation of China: The First Chinese

The First Chinese

By Dr. Clyde Winters

Edited by Ogu-Eji-Ofo-Annu

It can be reasonably assumed that the first inhabitants of the chinese mainland were Black Brown Africans from East, West and Central regions of Africa given that the earliest human skeletal remains in China are of “Negro” (or “Negritosâ€� a psuedo-scientific term commonly used today) people. The next oldest skeletal type after the period of predominance of the African immigrants were the Classical Mongoloids or Austronesian speakers.

Archaeological research makes it clear that “Negroids” (read: Central African skeletal types) were very common to ancient China. F. Weidenreich in Bull. Nat. Hist. Soc. Peiping 13, (1938-30) noted that the one of the earliest skulls from north China found in the Upper Cave of Chou-k’ou-tien, was of a Oceanic Negroid/ Melanesoid ” (p.163). This is the so-called Peking Man. This would place people in China during the Mesolithic looking like African/Negro people , not native American.

These Blacks were the dominant group in South China. Kwang-chih Chang, writing in the 4th edition of Archaeology of ancient China (1986) wrote that:” by the beginning of the Recent (Holocene) period the population in North China and that in the southwest and in Indochina had become sufficiently differentiated to be designated as Mongoloid and OCEANIC NEGROID races respectively….”(p.64). By the Upper Pleistocene the Negroid type was typified by the Liu-chiang skulls from Yunnan (Chang, 1986, p.69).

Negroid skeletons dating to the early periods of Southern Chinese history have been found in Shangdong, Jiantung, Sichuan, Yunnan, Pearl River delta and Jiangxi especially at the initial sites of Chingliengang (Ch’ing-lien-kang) and Mazhiabang (Ma chia-pang) phases (see: K.C. Chang, The archaeology of ancient China, (Yale University Press:New Haven,1977) p.76) . The Chingliengang culture is often referred to as the Ta-wen-k’ou (Dawenkou) culture of North China. The presence of Negroid skeletal remains at Dawenkou sites make it clear that Negroes spread out from the North to South China. The Dawenkou culture predates the Lung-shan culture which is associated with the Xia civilization.

Many researchers believe that the Yi of Southern China were the ancestors of the Austronesian, Polynesian and Melanesian people.

In the Chinese literature the Blacks were called li-min, Kunlung, Ch’iang (Qiang), Yi and Yueh. The founders of the Xia Dynasty and the Shang Dynasties were blacks. These blacks were called Yueh and Qiang. The modern Chinese are descendants of the Zhou. The second Shang Dynasty (situated at Anyang) was founded by the Yin. As a result this dynasty is called Shang-Yin.

The Yin or Classical/Oceanic Mongoloid type is associated with the Austronesian speakers ( Kwang-chih Chang, “Prehistoric and early historic culture horizons and traditions in South China”, Current Anthropology, 5 (1964) pp.359-375 :375). Djehuti your Austronesian or Oceanic ancestors were referred to in the Chinese literature as Yin, Feng, Yen, Zhiu Yi and Lun Yi.

It is not clear that contemporary European and Chinese people are descendants of the original Black population which lived in Europe and Asia; neither is it clear that the Chinese are descendants of the Austronesian speaking people.

Textual evidence and the skeletal record seem to indicate that contemporary Chinese and European people come out of nowhere after 1500 BC, the European Sea People came from the North and attacked Egypt, and the Chinese (Hua) people came from the North and ran the Black Qiang and Yueh tribes, along with the Austronesian Yin (classical mongoloid or Austronesian speakers) off the Chinese mainland back into Southeast Asia or on to the Pacific Islands.

You are reading Rasta Livewire. For all things Africa, visit AfricaResource: The Place for Africa on the Net.

No comments:

Post a Comment